Democracy can sometimes produce a range of unintended consequences. Without a doubt the recent referendum in the UK is one such event. The “leave” movement don’t have any real plans as to how nearly 40 years of integration will be undone within two years as provided for by Article 50 of the Lisbon treaty. The pound has been beaten down along with financial markets around the world adjusting very rapidly to a “risk off” trade following the outcome. Newspaper headlines are replete with scaremongering and drama as they are wont to do. The question we ask ourselves: “Is this a short term reset by financial markets as was the case with the Eurozone crisis in 2013, or do the issues in focus today have a more lasting impact on the macro economic picture going forward?”

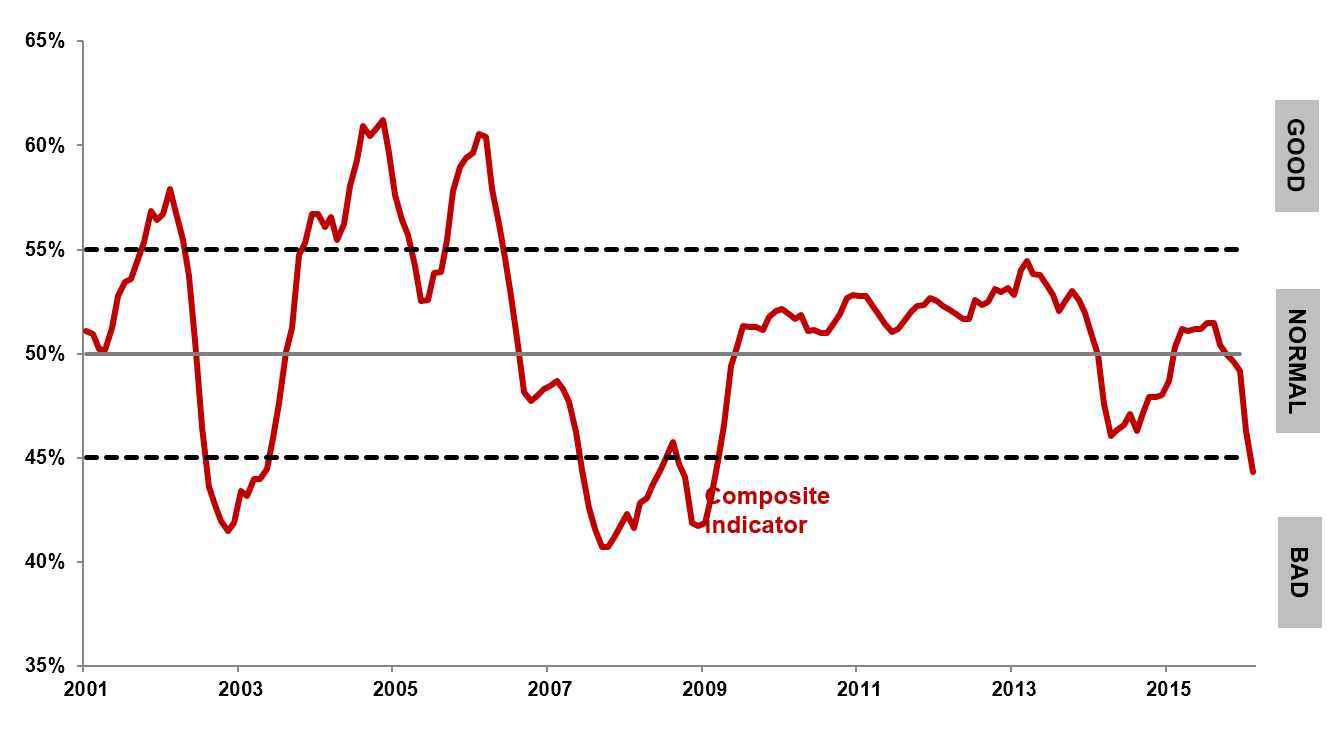

Chart 1: Global Composite Macro Indicator

Source: Vunani Fund Managers

As shown in chart 1 above, the VFM Composite Macro Indicator is heading lower. At its current level, the indicator points towards further deflationary pressures, slower economic and corporate earnings growth and a general need by central banks to remain accommodative. The deterioration in the indicator, coupled with recent events in the UK, potentially point to the end of the “reflation trade” that began earlier in the year when the Fed moved to a more dovish position on the dollar and China and the Eurozone introduced fresh rounds of stimuli. These observations notwithstanding, central banks may have to change tack in the post-Brexit era. Over the course of the past nine years (yes, it has been that long already) central bank intervention has taken the form of (a) rescuing the banks, (b) buying bonds and other financial assets in order to keep the financial system liquid and reduce long term yields as the primary mechanism for stimulating the wealth effect, and (c) keeping the spigots open for as long as is required to get retarded economies going. Whilst the sceptics will look back and say that the Friedman / Bernanke intervention has failed to adequately stimulate growth and has therefore failed to achieve the primary objective of reflating the global economy, the argument fails to acknowledge the alternative scenarios. Although successive rounds of quantitative easing have not produced the desired level of growth and indeed inflation, quantitative easing has been an important backstop to global liquidity in both financial markets and the banking system. A more incisive examination of global macro economic data reveals the true reason for the lack of economic growth – limited credit uptake by consumers and corporates. The world is experiencing something of a savings glut that is not offset through consumption or investment spending. Too much savings coupled with too little credit demand drives interest rates lower as savers compete for the highest rate. In a world where capacity is in surplus and demand is not rising, prices of goods and services struggle to find higher levels, resulting in policymakers having to consider a full suite of options in order to try to stimulate final demand. One such option is direct intervention in currency markets in order, mostly, to weaken the currency to compensate for weak domestic labour markets by boosting exports. But, as becomes evident rather quickly, countries then end up competing with each other as the game of competitive devaluation becomes a relative one. Japan has spent the best part of the past 15 years weakening its currency and increasing its debt to GDP ratio in order to reflate its economy. It has failed to do so as an ageing population continues to maintain high levels of savings and companies struggle, for cultural reasons, to let employees go. In a similar vein the eurozone is struggling with its own version of the “great contraction”. Unemployment rates in peripheral eurozone remain high with labour rates having fallen sharply. Savings rates have climbed as concerns around job security remain rather elevated. The credit cycle in most eurozone countries is still tepid with banks adopting a conservative lending policy – partly as a result of credit policies but also as a result of the more restrictive policy measures imposed by regulatory changes, in particular Basel III. The Brexit vote will not assist.

Examining the impact of Brexit on the eurozone is both nuanced and complex. With many countries highly dependent on the eurozone for trade flows, exiting is not the obvious option. What about Italy? The problem that countries such as Italy face is that the ECB has a limited number of ways in which it can assist in addressing the problems associated with a high debt burden, shrinking work force, and deteriorating competitiveness. In traditional economic theory the way in which these problems would be dealt with include currency depreciation and lower interest rates (including negative interest rate policies) or implementation of structural reforms via wage cuts to gain competitiveness. Alternatively, Italy could do what Japan has done over the past twenty years, which is to run persistently large budget deficits, effectively allowing the government to soak up the excess savings generated by the private sector. But these options are limited as investor interest in buying Italian debt on the cheap if the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio is on a course to eclipse Greece’s is likely to be limited.

This leaves one last option, which is to try to engineer higher inflation. A higher inflation rate would reduce the real rate of interest, even if nominal rates do not budge. The catch here is that a concerted move to raise inflation in the euro area will likely require the adoption of helicopter money policies – policies that the ECB regards as firmly outside its purview. As indicated before, we believe that the ECB will change its position over time and may do so more quickly now that Brexit has happened and France and Italy must be champing at the bit. In some ways the ECB may have to implement policies to avert investors turning negative on peripheral yield spreads. With Italian and Spanish bonds trading at yields that are lower than those in the US, spreads between peripheral eurozone bonds and the US / Germany may well start to increase if investors demand higher yields on the basis that Italy may jettison the common currency.

In the final analysis, the Brexit vote could not have come at a more inopportune time. Its impact on currency market stability, its contribution to a further deflationary pulse and the way it ushers in a new era of protectionism are all factors that are likely to make to job of central banks even more difficult. To end on a positive note one also needs to consider this as a first step in exploring other possibilities. After all, when nothing is sure, everything is possible.

Source: Tony Bell – KI, MiPlan; Fund Manager & CIO, Vunani Fund Managers